What do a Disney movie, a fascist Belgian newspaper, and The Great Gatsby have in common?

Take your guess and keep reading to find out! Hint: it’s not thinly veiled social commentary. Though that might be true as well.

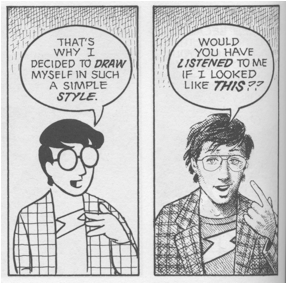

In Scott McCloud’s masterpiece Understanding Comics, he talks about a technique in illustration called “the masking effect.” (Here are two good articles about it, if you want to go more in depth.) The underlying principle is this: people want to see themselves in other things. But the more realistic or detailed a drawing of a person gets, the fewer people can see themselves in that person. A smiley face can apply to everyone, but a photo can only apply to one person. Thus, we project ourselves onto cartoony (simply drawn) characters, not realistically drawn ones.

To capitalize on this human tendency to see themselves in other things, and to make characters more relatable, illustrators and comic artists will draw their main characters more simply than their surroundings. Scenery and other people are often more detailed than main characters. Ever noticed how, in Disney movies, the main characters are drawn more simply than the supporting characters and the backgrounds? Yeah, that’s the masking effect at work. Disney wants you to identify with Belle and experience the provincial town through her eyes.

As you can see, the background is more three-dimensional and realistic than the foreground characters. And even the other characters have more complex facial features than our protagonist, Belle.

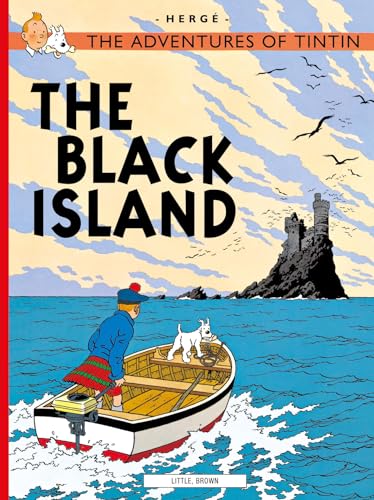

The masking effect is also used in the Tintin comics by Hergé. Tintin, a young reporter, was originally part of a serialized comic in a Belgian fascist newspaper warning against the dangers of the USSR. Hergé took his youthful protagonist to much greater heights, publishing many comic books featuring the popular hero and pioneering the “ligne claire” drawing technique.

Here’s a picture of Tintin–he’s basically a smiley face with a tuft of hair.

Here are pictures of other characters and backgrounds in Tintin.

The backgrounds are very detailed, and the other characters have more distinctive features. Out of everything in the comic, Tintin is the most simply drawn.

As you can see, the masking effect is used effectively in animated movies and comics. The viewer identifies with the character and see things through their eyes.

Lately, I’ve been wondering if the masking effect can be used in literature, too. Writers are told to make their characters interesting, fleshed-out, and fully developed. But can a bland, simplified main character pull a reader into a story? Can readers project themselves onto a boring main character?

Just what can a boring main character do for a story?

I’d say that boring main characters force the reader’s attention outward. Instead of focusing on the POV character, the reader will turn toward the setting and other characters.

Let’s look at a real literary example of the masking effect at work–Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby.

Nick is really boring. He’s a 30-year-old businessman who lets other people push him around and tell him what to do. He doesn’t have any goals–he aimlessly takes what he gets. He’s not especially kind or cruel, smart or dumb, rich or poor. He’s just sort of…there. You could basically replace him with a lawn ornament in Gatsby’s front yard.

So we read on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into Nick’s blandness. Why do we keep reading, though? Why do we put up with Nick’s self-righteous twaddle and vague non-judgments?

We keep reading because the book isn’t about Nick. It’s about Gatsby–him and Daisy, Tom and Jordan, and their appalling, racy, empty life on Long Island. We see West Egg and East Egg and the Valley of Ashes from Nick’s perspective. Nick is so bland that we can all project ourselves onto him. We can all be pinwheels and tin flamingos and gnomes in Gatsby’s front yard, and we can make the judgments that Nick refuses to say outright.

I’d also argue that Watson from the Sherlock Holmes stories exhibits the masking effect–though not as dramatically as The Great Gatsby. Watson is smart and brave and awesome, but he’s more ordinary than Holmes. We’ll identify with Watson’s feelings of bafflement and awe towards Holmes, and we’ll feel like we’re right there alongside Holmes as he cracks the case.

Basically, the masking effect works in illustration by making the viewer see everything from the protagonist’s point of view. In literature, the masking effect works by making the reader focus not on the protagonist but on the plot, setting, and supporting characters.

What do you think? Can you think of any examples of the masking effect, either in literature or elsewhere? Let me know in comments!

Featured image from Unsplash.

Cant think of an examples, except the ones already mentioned.. But what a killer post. So informative.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much!

LikeLike

Arthur Dent in “The Hitchhiker’s Guide To the Galaxy” seems to fit the bill of a boring main character

LikeLiked by 1 person

He totally does! Great observation! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a great observation. I’ll have to experiment with this in future sketches. I generally have “resonant” characters turn away so they are looking in the same direction as the viewer, but I’ll have to give simplified facial features a try.

Really appreciate this post. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you! If you liked this post, you should definitely give “Understanding Comics” by Scott McCloud a read–it’s full of helpful observations about art, storytelling, and comics. I am not an artist but it has really helped me approach literature in different ways.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This post is so informative.

I never knew about the masking effect and the Watson example made me think into it deeply and i realised how subtly writers get our attention.

Thank you so much for this knowledge!

LikeLiked by 1 person

No problem! Thanks for reading!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for bringing this very interesting effect to my attention! I’m not very familiar with comics and haven’t ever heard of this effect, but I have definitely noticed it at work in Nick Carraway and Watson, as you mentioned here. I would venture to say that in most other works where, as in Sherlock Holmes and The Great Gatsby, the viewpoint character is not the protagonist, the masking effect is probably at work as well.

This doesn’t fit quite as well (because he is pretty well-fleshed-out, with a backstory and fears and desires etc.) but I’d say that something similar is also at work with Winston in 1984. We’re presented with a very bizarre and frightening and exaggerated world, so it helps to see it through the eyes of a character who is rather ordinary and unassuming.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I haven’t read 1984, but it sounds like you’re spot-on: the ordinary character makes us focus on the storyworld. Thanks for the example!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much for this thoughtful post. Really loved all the information, while reading this all I could do was laugh to myself as I thought of a character who very much fits the simple looks department.

https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=images&cd=&ved=0ahUKEwjJvo-tnPjUAhWl8YMKHbiMCjoQjRwIBw&url=http%3A%2F%2Forzzzz.com%2F15-reasons-why-saitama-from-one-punch-man-is-your-favorite-superhero.html&psig=AFQjCNEjpg6RZqC0Mpz4-gl9etIrvz3lDg&ust=1499552980578467

Saitama from onepunch man. Though his powers definitly don’t make him come across as someone you can be. haha

LikeLiked by 1 person

Funny that you should mention One Punch Man… I’d never heard of it until yesterday when my friend was talking about it! Yeah, anime uses the masking effect all the time. Great observation!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s so funny how once something comes up all the sudden it’s everywhere that’s awesome! If you like hilarious animes you should give it a try!! It’s on instant watch on Netflix!! And one of my favorite anime right now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hmmmm gonna be keeping an eye out for that now. Thanks . good read!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

I’ve thought about this myself but have never really put it into words. Great, great post. Watson from Sherlock Holmes is a good example–I don’t think the books would be quite as interesting from Sherlock’s POV (although, admittedly, I do think Watson is adorable).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! You’re totally right, Watson is the cutest 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

This post was thought provoking and well written. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading!

LikeLike